You know Kusama’s lots of dots - her infinity rooms are one of her many spotted spaces. They’re iconic installations that immerse the viewer, surrounding them by circles that enchant and encourage the viewer to feel outside of herself. The polka dot style is playful and Kusama’s colours are entrancing, yet there’s more beneath - A polka dot portrait of a fascinating artist’s psychological makeup.

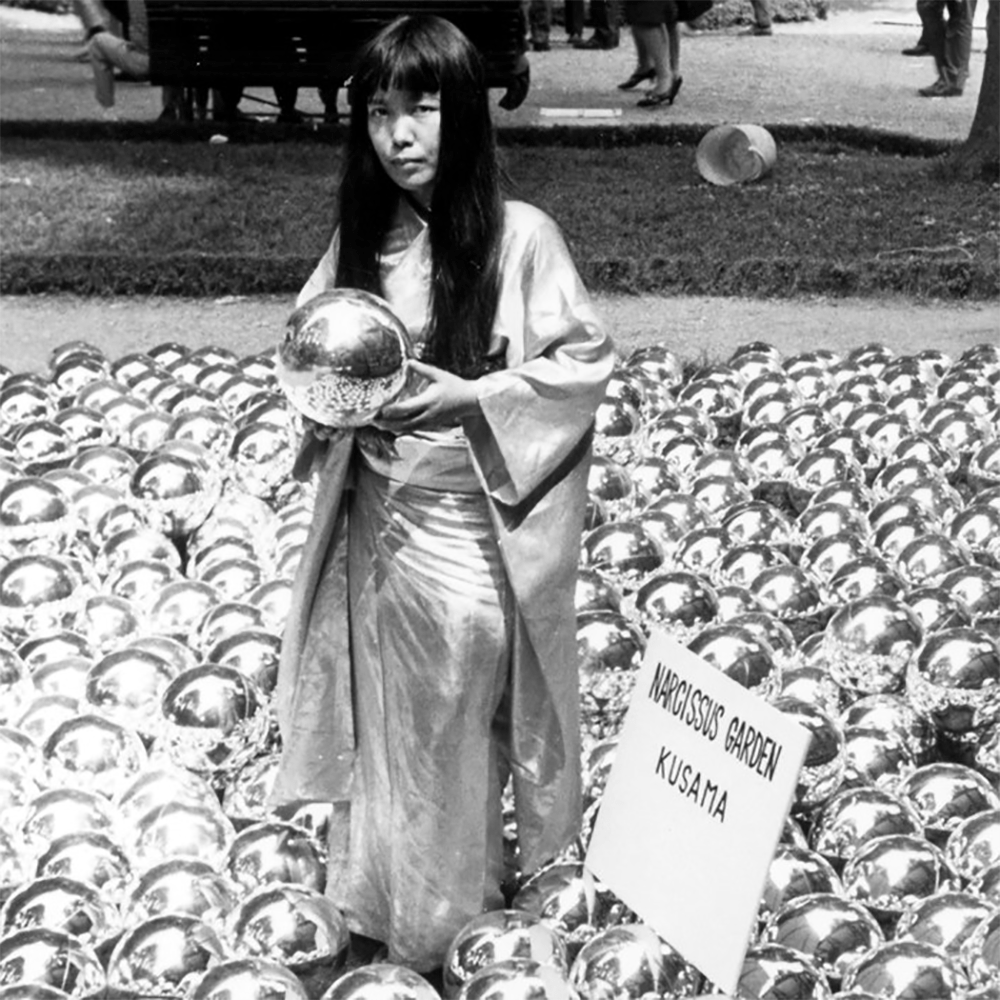

Photo Credit: MoMa

Photo Credit: MoMa

Photo Credit: MoMa

Photo Credit: MoMa

Photo Credit: Tate

Photo Credit: Tate

Photo Credit: MoMa

Photo Credit: MoMa

Photo Credit: Tate

Photo Credit: Tate

Shop The Look

Amalfi Coast Placemats - (Set of 6) Vibrant Dining, Italian Daydreams

Bring the coast to your tableInspired by sun-drenched terraces, painted...

£70.00 GBP

Standard price£56.00 GBP Membership price